The Warhol Copyright Case Hit the Supreme Court today, Here’s Why it’s Important

News | By Stephan Jukic | October 13, 2022

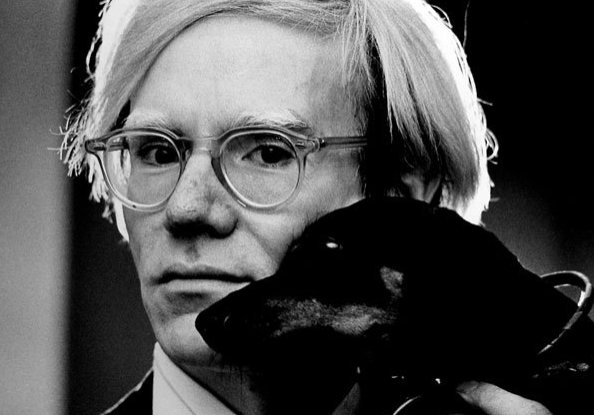

Andy Warhol by Jack Mitchell, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Renowned celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith has spent decades shooting some of the world’s most iconic and biggest names in music and the arts.

Among the many, many famous faces she’s captured in stunning, often extremely candid, and intimate moments are performers such as Bruce Springsteen, the Rolling Stones, Blondie, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Ozzy Osbourne, Sting and Prince, among others.

Curiously, a photo she took of Prince decades ago is what has more recently detonated a copyright case that has been snaking its way through the court system for several years now until today, when it finally reached the supreme court itself.

Goldsmith’s specific argument before the supreme court, against the counterclaim being put forth by the Andy Warhol Foundation, could upturn the underpinnings of how artists, photographers and creatives of all kinds can build upon other’s material for years to come.

The photo in question, a portrait shot of Prince captured during a brief NYC studio session all the way back in 1981, was later used by the famous pop artist Andy Warhol in one of his own illustrations. In 1984, for $400, the magazine Vanity Fair licensed a specific Prince photo Goldsmith had taken in 1981.

This picture was then used in an article titled “Purple Fame”. What Vanity Fair didn’t tell Goldsmith was that Warhol used her photo as a reference for one of his artworks. She also didn’t learn until much later that Warhol then used the same photo as the basis for a further 16 artworks of his that were titled the “Prince Series”. Of these, 14 were silkscreen prints and 2 were pencil drawings.

A selection of Warhol’s Prince works

For convoluted reasons, Goldsmith only found out about how her own photo was used decades later in 2016 after, Condé Nast, the parent company of Vanity Fair contacted the Andy Warhol Foundation for permission to use one of Warhol’s 1984 images that had originally been derived from Goldsmith’s 1981 photo. The AWF obliged and the image was featured on the May 2016 cover of the magazine with a credit to the AWF, but not to Goldsmith herself for her original photo.

Once the photographer noticed that it was her own photo that was used for Warhol’s famous Prince illustration (then featured on the magazine cover with an AWF credit), she informed the foundation that Warhol’s work infringed on her original photo copyright and promptly registered that original photo as an unpublished work with the U.S copyright office.

Early in the following year, before she could file a copyright infringement lawsuit of her own against the AWF for what it had previously done, the organization preemptively sued her instead, on the grounds that she had “attempted to extort a settlement” from the AWF for works that were fully governed under fair use clauses in copyright law.

Essentially, the AWF claimed that Warhol’s original works, admittedly inspired by Goldsmith’s photo, are however substantially different enough to be unique works in their own right. As the AWF’s estate lawyer noted in the original 2017 suit against Goldsmith, “As would be plain to any reasonable observer, each portrait in Warhol’s Prince Series fundamentally transformed the visual aesthetic and meaning of the Prince Publicity Photograph.”

Goldsmith’s original photo and Warhol’s derivative

Goldsmith then countersued the foundation but in July 2019, the presiding judge ruled in the AWF’s favor regarding its fair use claim.

This prompted Goldsmith to appeal the ruling and as it turned out, a judge then ruled in her favor this time, and despite the Warhol artwork being a heavily colorized image that was created with different materials and shading, Goldsmith won in her court argument that the paintings weren’t actually protected by fair use.

This and other court back-and-forth proceedings eventually went in Goldsmith’s overall favor, prompting the AWF, which had dug in its heels, to finally escalate everything to the Supreme Court itself. The interesting thing here is that the Supreme Court indeed agreed to take up the case and is deliberating on it today, October 12th.

This means that the top U.S court considers the case important enough for an opinion and has something it wants to say.

The AWF is obviously an organization with some cultural influence, but on the side of Lynn Goldsmith are also plenty of influential supporters.

Among those who have submitted opinions defending Goldsmith’s arguments include the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP), the National Press Photographer’s Association (NPPA) and even the United States Copyright Office itself.

The Copyright office’s involvement is the most significant detail of all here because it’s so unusual in what ostensibly amounts to just a legal dispute between two private parties. However, the ruling itself will have a major long-term impact for artists and photographers of all kinds in many industries and niches.

This is especially the case because the Supreme Court is the highest in the United States, and one of the more legally influential courts in the world.

How photographers and other artists are affected by the Goldsmith vs. AWF case will depend in part on how they operate creatively and commercially.

Should the AWF win, the definition of fair use, which has been a safe haven for many artists who derive their own works from others’ previous works, will be strengthened considerably at the cost of how much scope copyright has.

Should Goldsmith win, copyright protections for photographers and other artists will strengthen, but at the cost of creative license in reinterpreting an enormous amount of previously produced artwork that’s often used as a foundation for new works by new players.

As a recent Atlantic article on the Goldsmith vs. AWF case noted,

“Consider instances that survived fair-use challenges: posters for Grateful Dead concerts in a book about the band’s history; the hilarious movie poster for Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult, which parodied Annie Leibovitz’s famous photograph of Demi Moore; playing John Lennon’s “Imagine” in a documentary about the perception of religion in popular culture. Our cultural history is plainly richer as a result of these integrations, just as it’s richer with Warhol’s image in it.”

The Atlantic piece also notes,

“any shrinkage in fair use creates chilling effects around the edges of the actual border. Content creators, especially independent ones who don’t have access to legal counsel, not only will abstain from doing the precise thing banned by the Court (e.g., drawing something based on a photo), but will also fear doing anything that approaches that particular use. In practice, it’s not just the specific use that will be attacked, but the entire class of similar uses.”

If you’re a photographer, it’s easy at first glance to side with Goldsmith’s case, but it’s worth pausing too: Many photographers are more than just simple photographers, and in many cases, much of their eventual artistic output involves deriving creations from something done by someone else that inspired them.

A scaled-back fair use definition could weaken the ability to do that while not really improving protections against many common types of artistic exploitation that most photographers face much more often than what Lynn Goldsmith is arguing against in this case.

Check out these 8 essential tools to help you succeed as a professional photographer.

Includes limited-time discounts.